Protocol Buffer Syntax and Encoding Principles

[toc]

Serialization refers to the process of converting structured data into a format that is easy to store or transmit.

Protocol Buffer, abbreviated as ProtoBuf, is a language- and platform-independent serialization tool developed by Google and open-sourced in 2008. Compared to commonly used serialization tools such as XML, JSON, YAML, and CSV, ProtoBuf has advantages including smaller serialized data size, faster serialization and deserialization, lower maintenance cost through the use of proto files, and backward compatibility. However, because its data exists in the form of binary data streams, it also has the disadvantage of being unreadable to humans.

This article mainly introduces the usage of ProtoBuf, including the syntax of .proto files and how to use the protoc tool to generate code in different languages, as well as its encoding principles.

1 Syntax

First, download the latest version of ProtoBuf from https://github.com/protocolbuffers/protobuf, and extract the pre-compiled binary file protoc to the environment variable directory. This article uses version 3.15.7:

$ protoc --version

libprotoc 3.15.7

Taking a simple proto file as an example, its syntax is similar to that of C++:

// msg.proto

syntax = "proto3";

package Message;

message SearchRequest {

reserved 6, 9 to 12;

reserved "foo", "bar";

string query = 1;

int32 page_number = 2;

int32 result_per_page = 3;

}

message ResultType {

message Result {

string url = 1;

string title = 2;

repeated string snippets = 3;

}

}

message SearchResponse {

repeated ResultType.Result results = 1;

}

Use the protoc tool to generate code in the specified language:

protoc --proto_path=./ --go_out=./go_out/ --cpp_out=./cpp_out/ msg.proto

Here, --proto_path or -I is used to specify the directory where the required proto files and imported proto files are located. If not specified, the current directory is used by default. go_out and cpp_out are used to specify the directories for the generated go and cpp files, respectively. Finally, all proto files that need to be converted are specified. More parameters can be viewed by entering protoc --help.

1.1 Data Structure

The msg.proto file contains two parts: first, the version of ProtoBuf needs to be specified as proto3. If not specified, the compiler will default to using the old version of proto2 syntax. Then, we define the message types we need. Each message type has many fields, and each field corresponds to a unique number, which is used to identify the field in the serialized binary data stream.

Fields and Numbers

Fields are divided into two types:

- Singular: the default type of a field, where the field can only have 0 or 1 data;

- Repeated: similar to an array, where the field can have any number of data, and the order is preserved.

When mapping fields to numbers, the following points need to be noted:

- We can use any number in the range [1, 19000) and (19999, 2^29 - 1] to identify fields. The range [19000, 19999] is reserved for ProtoBuf implementations;

- When encoding proto files, numbers 1 to 15 occupy 1 byte, and 16 to 2047 occupy 2 bytes. Therefore, commonly used fields are generally mapped to numbers 1 to 15 to save space;

- Once a number is used, the type of the corresponding field cannot be changed, otherwise it will cause compatibility issues.

Composition and Nesting Structures

We can directly nest and use another message structure within a message type:

message SearchResponse {

message Result {

string url = 1;

string title = 2;

repeated string snippets = 3;

}

repeated Result results = 1;

}

If we want to use a child message type nested in another message type, we need to add the parent message type’s name when defining it:

message ResultType {

message Result {

string url = 1;

string title = 2;

repeated string snippets = 3;

}

}

message SearchResponse {

repeated ResultType.Result results = 1;

}

Similarly, we can introduce another message type as a field in a message type in a composite way and assign it the repeated property. If the imported message type is in another proto file, we need to import the corresponding file:

// msg.proto

import "result.proto";

message SearchResponse {

repeated Result results = 1;

}

// result.proto

message Result {

string url = 1;

string title = 2;

repeated string snippets = 3;

}

import

There are two ways to use import: one is to import using a relative path, as in the example above; the other is to use the -I command when generating code with the protoc tool to specify the directory where the proto files are located and import them using an absolute path:

$ tree

.

|-- msg.proto

`-- result

`-- result.proto

1 directory, 2 files

$ protoc -I. -I./result/ --go_out=./ msg.proto

1.2 Keywords

Packages

The purpose of a package is to avoid naming conflicts between different ProtoBuf messages, similar to the namespace in C language:

package Message;

Services

A service is used to define the message types used in RPC. gRPC has extensive use of services, and its definition is similar to defining functions in Go:

service SearchService {

rpc Search (SearchRequest) returns (SearchResponse);

}

Options

Options can change the way some predefined contexts in the proto file are processed, including but not limited to:

optimize_formodifies the code generation method and has three types:SPEEDfor high optimization,CODE_SIZEfor reduced code, andLITE_RUNTIMEfor simplified functionality;packedgenerates more compact code for repeated fields;deprecatedis used for fields that have been deprecated and generally only generates comments. It should be used with thereservedkeyword as much as possible.

option optimize_for = CODE_SIZE;

// ...

repeated int32 samples = 4 [packed=true];

int32 old_field = 6 [deprecated=true];

Version Compatibility

To make new versions of proto files compatible with older versions, we cannot modify the type of any existing fields to prevent compatibility issues when using old code to parse new data structures.

When we no longer use certain fields, we can delete or comment out both the field and its corresponding number. To prevent accidentally reusing the same number and corresponding to a different type of field, we can use the reserved keyword to mark the deleted fields and numbers and let the compiler check whether these fields and numbers have been reused during compilation:

// msg.proto

message SearchRequest {

reserved 3, 6, 9 to 12;

reserved "foo", "bar";

string query = 1;

int32 page_number = 2;

int32 result_per_page = 3;

}

$ protoc -I. --go_out=./ msg.proto

msg.proto: Field "result_per_page" uses reserved number 3.

1.3 Data Types

Primitive Types

The following list shows all the primitive data types that can be used in proto files:

| Type | Default Value | Description | C++ Type | Python Type | Go Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| double | 0 | double | float | float64 | |

| float | 0 | float | float | float32 | |

| int32 | 0 | Encoded using varint, so it is recommended to use sint32 for negative numbers | int32 | int | int32 |

| int64 | 0 | Encoded using varint, so it is recommended to use sint64 for negative numbers | int64 | int/long[3] | int64 |

| uint32 | 0 | Encoded using varint | uint32 | int/long[3] | uint32 |

| uint64 | 0 | Encoded using varint | uint64 | int/long[3] | uint64 |

| sint32 | 0 | Encoded using varint, signed | int32 | int | int32 |

| sint64 | 0 | Encoded using varint, signed | int64 | int/long[3] | int64 |

| fixed32 | 0 | Fixed 4 bytes, more efficient than uint32 for values over 228 | uint32 | int/long[3] | uint32 |

| fixed64 | 0 | Fixed 8 bytes, more efficient than uint64 for values over 256 | uint64 | int/long[3] | uint64 |

| sfixed32 | 0 | Fixed 4 bytes | int32 | int | int32 |

| sfixed64 | 0 | Fixed 8 bytes | int64 | int/long[3] | int64 |

| bool | false | bool | bool | bool | |

| string | "" | Must be encoded in UTF-8 or 7-bit ASCII, and length can’t exceed 232 | string | str/unicode[4] | string |

| bytes | "" | Any byte sequence with length not exceeding 232 | string | str | []byte |

In addition to these basic types, the default value for enum types is 0 (the first defined enum value), and the default value for repeated fields is empty.

map

One of the highlights of ProtoBuf is that it has a built-in map data type, where key_type can be any integer type or string type:

map<key_type, value_type> map_field = N;

Currently, map cannot be modified by repeated, but its effect can be achieved by customizing a map-like structure. The mapping relationship from key_type to value_type needs to be solved manually:

message MapFieldEntry {

key_type key = 1;

value_type value = 2;

}

repeated MapFieldEntry map_field = N;

Enum Types

The enum type definition in the proto file is roughly as follows:

message EnumRequest {

enum Corpus {

option allow_alias = true;

UNIVERSAL = 0;

WEB = 1;

NET = 1;

IMAGES = 2;

LOCAL = 3;

}

Corpus corpus = 1;

}

There are several points to note when using enum types:

- Enum values must be within the range of 32-bit integers and negative values are not recommended (because enum values are encoded using varint during serialization);

- There must be an enum variable with a value of 0 in the enum type definition;

- If you want to define enum types with the same value, you must add

option allow_alias = true.

Special Types

In addition to basic data types such as double, float, and int32, some special data types can also be defined in proto files:

Anycontains a serialized message of any number of bytes;Oneofis similar tounion, which means that multiple fields share the same memory block, and only one of them can be assigned a value.

2 Encoding Process

The encoding process of ProtoBuf is divided into two parts: first encode the definition of the field to identify its type during the decoding process; then encode the value of the data and compress it. The first part actually uses certain rules to encode the type and number of the field to obtain the field’s tag, and the field name is not used, so even if the field name is modified in actual use, there will be no compatibility issues; the second part uses different algorithms to compress the data of different types to obtain the value, and the two main algorithms used are Varint and ZigZag. After completing these two parts of encoding, concatenate the tag, byte length (only for variable-length types), and value together to obtain the encoded binary data.

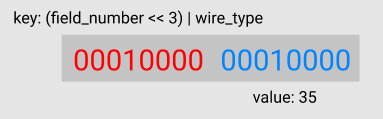

2.1 Tag Encoding

The encoding process of the tag is to first map the field type to a wire_type number, and then left shift the field number by 3 bits, and perform bitwise OR with the wire_type, that is, (field_number << 3) | wire_type. The mapping relationship between the field type and wire_type is as follows:

| wire_type | Meaning | Storage structure | Corresponding field type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Use Varint compression | [Tag Value] | int32, int64, uint32, uint64, sint32, sint64, bool, enum |

| 1 | 64-bit | [Tag Value] | fixed64, sfixed64, double |

| 2 | Distinguished by length | [Tag Length Value] | string, bytes, embedded messages, packed repeated fields |

| 3 | Start group | groups (deprecated) | |

| 4 | End group | groups (deprecated) | |

| 5 | 32-bit | [Tag Value] | fixed32, sfixed32, float |

When decoding, it is necessary to provide the correct proto file in order to obtain the definition of the storage structure.

For example, if you want to encode a field with field_number = 2 and field type sint64, with wire_type = 0, you can know that (field_number << 3) | wire_type = 10000, which is encoded as 10;

Similarly, during decoding, the last three bits are first extracted using & 111 to obtain the wire_type = 0, and then right-shifted by 3 bits to obtain the field_number = 2.

In summary, for the bytes encoded for a field, the last three bits represent the type, and the preceding bits represent the field number.

2.2 Varint

Varint is the main encoding method for integers with WireType == 0. The binary length of data encoded with Varint is not fixed, and the smaller the value of the number, the smaller the length of the encoded bytes. The encoding process consists of three steps:

- For the binary representation of a number, split it into groups of 7 bits each.

- Add a most significant bit (msb) to the beginning of each group, with the msb of the largest group equal to 0, and the msb of all other groups equal to 1.

- Arrange these bytes in little-endian order.

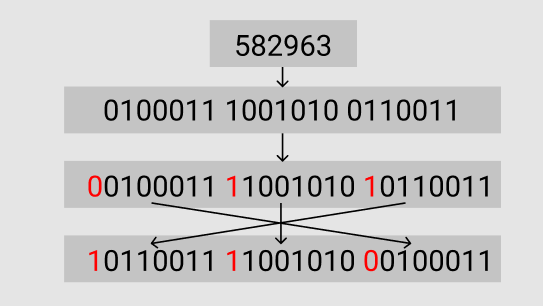

For example, let’s take the number 582,963:

- Its binary representation is 10001110010100110011, which can be split into three groups: 0100011, 1001010, and 0110011, which represent 35, 74, and 51, respectively.

- Add an msb of 0 to the largest group to get 00100011 (still 35), and add an msb of 1 to the other two groups to get 11001010 and 10110011, which represent 202 and 179, respectively.

- Arrange these three bytes in little-endian order to get 10110011 11001010 00100011, which represent 179, 202, and 35, respectively. This is the final result obtained by encoding with Varint.

varint

Testing encoding of number 582963 using ProtoBuf:

message SingleNumber {

int32 Num = 1;

}

func main() {

sn := SingleNumber {

Num: 582963,

}

bytes, err := proto.Marshal(&sn)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(bytes)

}

The result obtained is the same as the steps mentioned above, where the first byte 8 is the key obtained by encoding the field:

$ go run main.go msg.pb.go

[8 179 202 35]

Decoding process is also similar:

func main() {

b := []byte{8, 179, 202, 35}

var sn SingleNumber

err := proto.Unmarshal(b, &sn)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(sn.GetNum())

}

$ go run main.go msg.pb.go

582963

2.3 ZigZag

The essence of Varint encoding is to remove leading zeros in the binary representation of a number in order to reduce the number of bytes used by the data. However, when it comes to negative numbers represented in two’s complement, using Varint for encoding would result in 5 bytes for a 32-bit number and 10 bytes for a 64-bit number, which is very inefficient. To optimize this, ProtoBuf uses ZigZag to map signed integers to unsigned integers. The encoding result of a positive number is equivalent to multiplying it by 2, while the encoding result of a negative number is equivalent to multiplying its absolute value by 2 and subtracting 1. The encoded value corresponds to the original data oscillating between positive and negative numbers, as shown in the table below:

| Signed Integer | Unsigned Integer Encoding |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| -1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| -2 | 3 |

| 2147483647 | 4294967294 |

| -2147483648 | 4294967295 |

Its process is also very simple:

- Assume that the binary representation of the encoded number is num, and shift num left by 1 bit to get x.

- Shift num right by 31 bits (the number of bits in num minus 1) to get y, that is, use the sign bit to cover each bit of num.

- Perform XOR operation between x and y to get the result

z = x ^ y.

For example, for the positive number 5:

- x = 5 « 1 = 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001010

- y = 5 » 31 = 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000

- z = x ^ y = 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001010, which is 10

For the negative number -5:

- x = -5 « 1 = 11111111 11111111 11111111 11110110

- y = -5 » 31 = 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

- z = x ^ y = 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001001, which is 9

In ProtoBuf, negative numbers are first encoded using ZigZag and then using Varint to achieve further data compression.

2.4 Other Encoding Processes

Variable-Length Types

For variable-length types (such as string, bytes, etc.) with WireType == 2, the serialized binary data stream is stored in the [Tag Length Value] format, where Length is the length of the variable-length part. For example:

message SingleNumber {

int32 Num = 1;

string Str = 2;

}

func main() {

sn := SingleNumber {

Num: 582963,

Str: "helloworld"

}

bytes, err := proto.Marshal(&sn)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(bytes)

}

$ go run main.go msg.pb.go

[8 179 202 35 18 10 104 101 108 108 111 119 111 114 108 100]

In the output, the fifth byte 18 is the Tag for string Str = 2, where field_num = 2, wire_type = 2; the sixth byte 10 represents the length of this variable-length type, which means that the value is stored from the seventh byte to the sixteenth byte, with each value being stored as an ASCII character.

Fixed-length types

For fixed-length types with WireType == 1 or WireType == 5 (such as fixed32, fixed64, etc.), the length of their serialized binary data is fixed at 4 or 8 bytes, respectively. For example:

message SingleNumber {

int32 Num = 1;

string Str = 2;

fixed32 A = 3;

fixed64 B = 4;

float C = 5;

}

func main() {

sn := SingleNumber {

// Num: 582963,

// Str: "helloworld",

A: 256,

B: 257,

}

bytes, err := proto.Marshal(&sn)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

fmt.Println(bytes)

}

$ go run main.go msg.pb.go

[29 0 1 0 0 33 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0]

In the resulting bytes, the first byte represents the tag of fixed32 A = 3, where field_num = 3, wire_type = 5, and the following 4 bytes are directly stored according to byte order. The fifth byte represents the tag of fixed64 B = 4, where field_num = 4, wire_type = 1, and the following 8 bytes are similarly stored directly according to byte order.